Because of zoning regulations known as parking minimums, which require a specific quantity of off-street parking for new projects, parking is so common in many American cities. Parking requirements may prevent cities from promoting transit-oriented development (TOD), a type of planning that encourages public transportation and lowers local emissions.

What is the history of parking minimums? Columbus, Ohio set the precedent for the first minimal parking requirement in 1923. Parking requirements had developed into a mainstay of American urban planning by the 1950s, serving as a catalyst for how the automobile would come to define the United States and the layout of its cities.

Today, I’m explaining what is parking minimums and the major problems with it. Keep reading!

Table of Contents

Introduction Of Parking Minimums

Parking minimums have, however, come under more scrutiny recently. Minimums restrict their options for developing projects by requiring them to invest significant amounts of money and land in providing parking, which frustrates and restricts developers who find them rigid and expensive. Parking minimums are coming under increasing fire from the planning community, who fear that they will maintain American cities’ auto-centricity, which prioritizes automobiles over people, housing, and high-quality architecture. Parking minimums, according to transportation planners, make cities and towns less walkable, resulting in longer travel times, a greater need for driving, and ultimately, more parking.

Late in the 1990s, planners and researchers, most notably UCLA Professor Donald Shoup, started to notice that municipal parking minimums required far more parking spaces than are typically needed, which had a negative impact on city policy goals. The environment for transportation is currently changing even more under the feet of planners. The preferences of consumers are shifting, and they now have more choices than just driving and parking. According to data, teenagers wait longer to obtain their driver’s licenses. The use of TNCs (transportation network companies), like Uber and Lyft, is increasing yearly. Even dockless scooters have had a significant impact in the past year.

Urban planners are therefore becoming more and more aware that parking requirements do not always support the planning principles, objectives, and need for more housing in their communities. In fact, they frequently accomplish opposing goals. The concept of parking minimums appears to be a rigid anachronism that has outlived its usefulness, given that Americans are becoming more specialized in their modes of transportation.

Urban Planning Factors

Usually, cities remove parking requirements in order to advance urban planning objectives. For instance, over the past ten years, many cities have made a concerted effort to promote the use of public transportation, bicycles, and foot travel as alternatives to private automobiles. Sustainability objectives served as a major driving force behind the promotion of transit. By limiting the number of cars and trucks on the streets, city planners and other leaders hoped to improve the environment in their neighborhoods. Less fuel is burned, less exhaust is produced, and less air pollution is released when there are fewer cars on city streets.

Moreover, removing or lowering parking requirements frees up more space for people and housing at a time when cities are increasingly struggling with a housing shortage. Additionally, since parking is expensive, eliminating irrational parking requirements lowers the cost of housing overall, especially when more housing can be constructed.

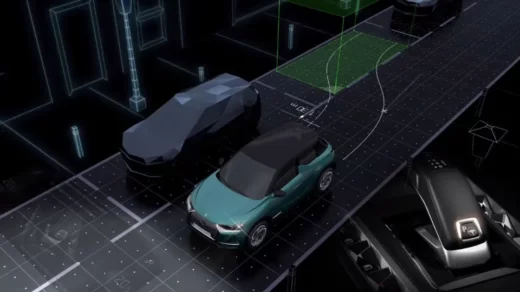

Future technological developments will also lessen the need for parking minimums. According to autonomous vehicle scenarios, the need for parking should decline over the next few decades by as much as 40%, with a minimum reduction of 10% occurring in urban areas. Even in a worst-case scenario, millions of cars would no longer be able to park where they do now. Instead of driving to cities today, commuters and tourists will be dropped off by self-driving TNCs, and owners of self-driving cars will have them sent to less expensive parking lots outside of crowded urban areas or sent home for the day. To get to the closest transit station, some people will use a shared autonomous vehicle.

The transportation system in America is evolving. This could be a revolutionary idea for parking planners. Urban parking demand will decline significantly, but new spaces, such as the curb, will also need to be planned for and managed to accommodate the sharp rise in pick-ups and drop-offs. It is simple to understand why these trends and the upcoming advent of the self-driving age are prompting city planners to reconsider the necessity of parking minimums.

And now is the time to change because cities must always look to the future. Cities must reevaluate the idea of parking minimums and their requirement for them because the planning and investment decisions made today will affect the infrastructure used in 50 years.

Making Parking Minimums Work

Although there is definitely a trend toward lowering parking requirements, there is no overarching pattern. This is due to the fact that each community is distinct, making it impossible to find a solution that applies to all. What is effective in San Francisco might not be effective in Chattanooga, Tennessee. It’s a matter of “right-sizing” parking to meet the distinctive needs of a particular community. If parking requirements are to be eliminated, plans must be in place to guarantee that there will be enough parking to meet demand.

Furthermore, just because a city lowers or does away with its parking requirements does not imply that less parking will be constructed. The planning community did not trust developers to provide enough parking, so parking minimums were initially adopted. However, the surroundings have altered. Because adequate parking is essential to successful development, most developers strive to do so. No developer wants their project to fail because they constructed either too few or too many parking spaces.

Additionally, while developers spend a sizeable portion of their capital budgets on parking, they are enhancing amenities that eliminate the need for car ownership. It is thought to be more effective, less expensive, and in line with the variety of transportation needs of today to divert parking funds to providing non-parking access to locations via car sharing, transit passes, and bike parking.

Parking and other access options will be available where they are required. How much will be provided, as well as in what manner?

The good news is that there are trustworthy tools and parking planning techniques that can ensure that communities (and the developers within those communities) are building the appropriate amount of parking so that commerce can flourish while, at the same time, managing the existing parking supply efficiently and effectively. Not only is this approach more cost-effective, but it also assures that valuable land can be used for more appropriate uses; parking is often not the desired “highest and best use,”, particularly in a dense urban or even suburban location.

Cities can use a number of different tactics to adapt to a reduction in parking requirements. To stop street spillover, any policy that lowers or eliminates parking requirements should be combined with specific on-street parking regulations. Generally speaking, moving to on-street spaces required for neighborhood business customers is not ideal for residents, employees, or other long-term parkers. Policies like parking fees, time limits, and active enforcement help and are frequently essential to the overall operation of the parking system, ensuring that valuable on-street parking spaces are available for guests and other customers.

In addition to enforcing rules regarding on-street parking, cities must control the increasing demand for curb space to effectively divide the time among the widening range of users vying for it. Compared to even a few years ago, there is a lot more activity at the curb between TNCs, bicycles, scooters, delivery vehicles, buses, and private cars. Although the use of public resources and assets is essential to their success, the private sector may be changing how people travel. Cities have the chance and duty to make the most of the resources at their disposal, such as curb access fees and regulations, in order to implement curb management strategies that support overall land use and mobility objectives. The timing of technological advancements is perfect for enabling curb management in cities. These tools can make it easier to use curb access fees, which help pay for investments in bike lanes, pedestrian enhancements, and public transportation. With dockless scooters, cities like Santa Monica, California, are setting the pace. TNCs, which have a greater impact on traffic congestion and the environment, and eventually autonomous vehicles should be subject to similar regulations.

Additionally, shared parking can be extremely useful in providing more flexible parking and less of it. In order for shared parking to function, parking owners must pool their resources. The mechanism takes advantage of the variations in peak parking demand caused by complementary land uses, allowing different users to share parking spaces.

For instance, a residential building that typically needs to provide the majority of its parking on the weekends and evenings can share parking facilities with an office building that primarily needs parking spaces during business hours. Without adding additional parking spaces for patrons, employees, residents, and even delivery drivers, parking owners can make the necessary accommodations with the help of a shared parking strategy. When cities permit shared parking they provide a cost-effective way to address parking

shortfalls using existing spaces, while increasing the capacity of 48 Every parking space in the system was journaled in February 2019. In addition to freeing up more space for purposes other than parking, this also lowers the overall cost of development, which may result in lower rents.

A city’s ability to eliminate parking requirements can, for obvious reasons, be significantly impacted by the effectiveness of its transit system. However, the advantages go both ways because parking management can produce income to support infrastructure for alternative modes of transportation like public transportation, bicycles, and pedestrians, further reducing the need for parking minimums. In Portland, Oregon, and San Francisco, for instance, parking fees go toward paying for transit. By enabling more people to walk from existing parking facilities to more destinations, good pedestrian infrastructure can also significantly increase the parking supply. A community’s need for parking may eventually be decreased if parking funds are used for other forms of transportation.

Major Problems With Parking Minimums

1. They Take Away Our Ability To Produce Money And Our Prosperity.

The majority of cities rely on property taxes to pay for municipal services like fire protection, schools, and streets, and the amount each property is taxed is determined by its assessed value.

That value is incredibly low for parking lots. We discover a significant loss in tax value when we multiply this calculation across all of our cities, where parking lots are mandated by law for the majority of properties. This translates to fewer police officers on the streets, fewer teachers in the classrooms, fewer potholes patched, street lamps fixed, and parks planted… and so on.

As our friend Josh McCarty, who has studied the tax value of parking in depth, writes, “The most crucial design element that lowers the tax productivity of development is parking, in the end. Parking should be treated as the dead weight that it is by municipalities whose existence depends on property taxes.”

2. Small-business Owners, Home Owners, Real Estate Agents, And Tenants Are All Hampered By Them.

Yes, parking requirements are detrimental to almost everyone. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Small business owners are forced to spend their precious, hard-earned dollars paying for designated parking spaces for their customers instead of spending that money on supplies, space to sell products, etc. Due to a lack of parking, they may also be completely barred from locating in some areas.

- Homeowners are prevented from taking on basic projects like adding a small rental unit in a basement or backyard because parking minimums would mandate the provision of parking space for the tenant of that unit (and the typical single-family lot doesn’t have room to add that).

- Developers are unable to execute projects because (similar to homeowners) a lack of space on a given lot may prevent them from constructing the required parking to accompany it, or (similar to business owners) they are forced to spend a large portion of their development budget on storage for cars instead of units for paying tenants. (Listen to our conversation with developer Monte Anderson to learn more about this subject.)

- Renters end up losing many housing opportunities because spaces that could be filled with homes are, instead, filled with parking.

3. They Saturate Our Cities With Wasteful, Empty Space.

This final point becomes abundantly clear on Strong Towns’ annual #BlackFridayParking Day when we invite our readers to venture out into their cities on one of the busiest shopping days of the year and snap photos of the parking lots nearby. Every November, we observe that even on this popular shopping day, cities after cities are brimming with unused, empty asphalt.

Parking lots not only take up space that could be used for a multitude of more useful purposes, but they also increase the distance between homes and businesses in our communities, making it more difficult to get to them and necessitating greater expenditures on roads, traffic lights, and other transportation infrastructure. A multi-mile drive once required only a short stroll between the grocery store and home; one of the main reasons for this is parking minimums.

At the end of the day, parking-heavy cities aren’t appealing, hospitable, or fun places to spend time. Imagine yourself visiting a thrilling, enjoyable location. It could be a bustling city or a charming beach town. Was there a sea of parking spaces between each building? I’m guessing not.

With parking minimums, we have prohibited what we value most, as architect Benjamin Ledford wrote last year. (View the photo on the right.) We have miles and miles of asphalt instead of family homes and flourishing businesses.

To sum up, parking minimums drain our cities of tax revenue, create obstacles for virtually everyone who lives or works in our neighborhoods, and leave us with a lot of empty, useless space.

Parking Minimums Is A Growing Trend

The decision to do away with parking minimums by planners and city officials in San Francisco, Buffalo, and Minneapolis is a step toward what should become standard practice in many cities over the coming few years. Parking minimums seem to be rigid holdovers from a bygone era in the modern world, where alternative modes of transportation and transit ridership are major policy goals and where shared parking is becoming necessary to accommodate new destinations. In the long run, eliminating minimums will greatly improve community quality of life, urban planning, and development. For this new minimum-free approach to succeed, however, data-driven decisions must be made and parking must be managed more effectively.

Chrissy Mancini Nichols works out of Walker Consultants’ San Francisco location. In order to meet the needs of various user groups and advance land use and mobility objectives, she collaborates with cities, agencies, and organizations on transportation, parking, and land-use planning, finance, and policy. She led a strategy to redevelop Chicago Union Station through a public-private partnership that includes $1 billion in station improvements. She created and passed a value capture district to fund over $10 billion in transit projects. She has contributed to several local and state public-private partnerships for airports, parking facilities, transit, and highways. As the national autonomous vehicle and TNC policy lead for Walker, she develops plans for curb management and revenue sharing.

Read More: Self-Driving Cars